When looking at the design possibilities for a VR production, it helps to first draw attention to the target audience:

ow do the users behave – alone or in community, in relation to different contexts, media and formats (such as museum, cinema, visual arts, theatre or video game)? How much influence do we allow the users and how much interaction is possible, how much is necessary? How do we turn passive viewers into active creators?

In the context of museums and exhibitions, we are used to choosing our own path and exploring a subject area according to our interests. Interaction with media and exhibits is commonplace; participation has become the supposed recipe for success. In the cinema, on the other hand, the audience becomes a pure consumer: interaction takes place (if at all) only between the spectators, the events on the screen cannot be influenced in any way. With conventional concert and theatre audiences, interaction is possible in the form of spontaneous expressions of applause or dislike; but also here, influencing the course of events on stage is not common. However, for a time there have already been experimental ways of playing that involve the audience to varying degrees. The audience is „activated“, can – or even has to – participate in the action and is able to influence the course of the plot. The theatre group Rimini Protokoll, for example, uses methods from game design to let the „theatre users“ interact with the production (see their work Situation Rooms). Some productions even do without actors at all and make the audience the main actor (100% Stadt). In video games, the participation and influence of the gamers is indispensable: Here, the interaction between medium and audience is an integral part of the format and is closely related to the phenomenon of (user) agency.

In contemporary art, a variety of strategies of audience participation can be observed since the 1960s and 1970s. Artists not only take the public into account, but also plan its participation from the very beginning and make it part of the artistic practice itself. Ultimately, the recipients help to shape the artwork, the performance or the piece through their participation.

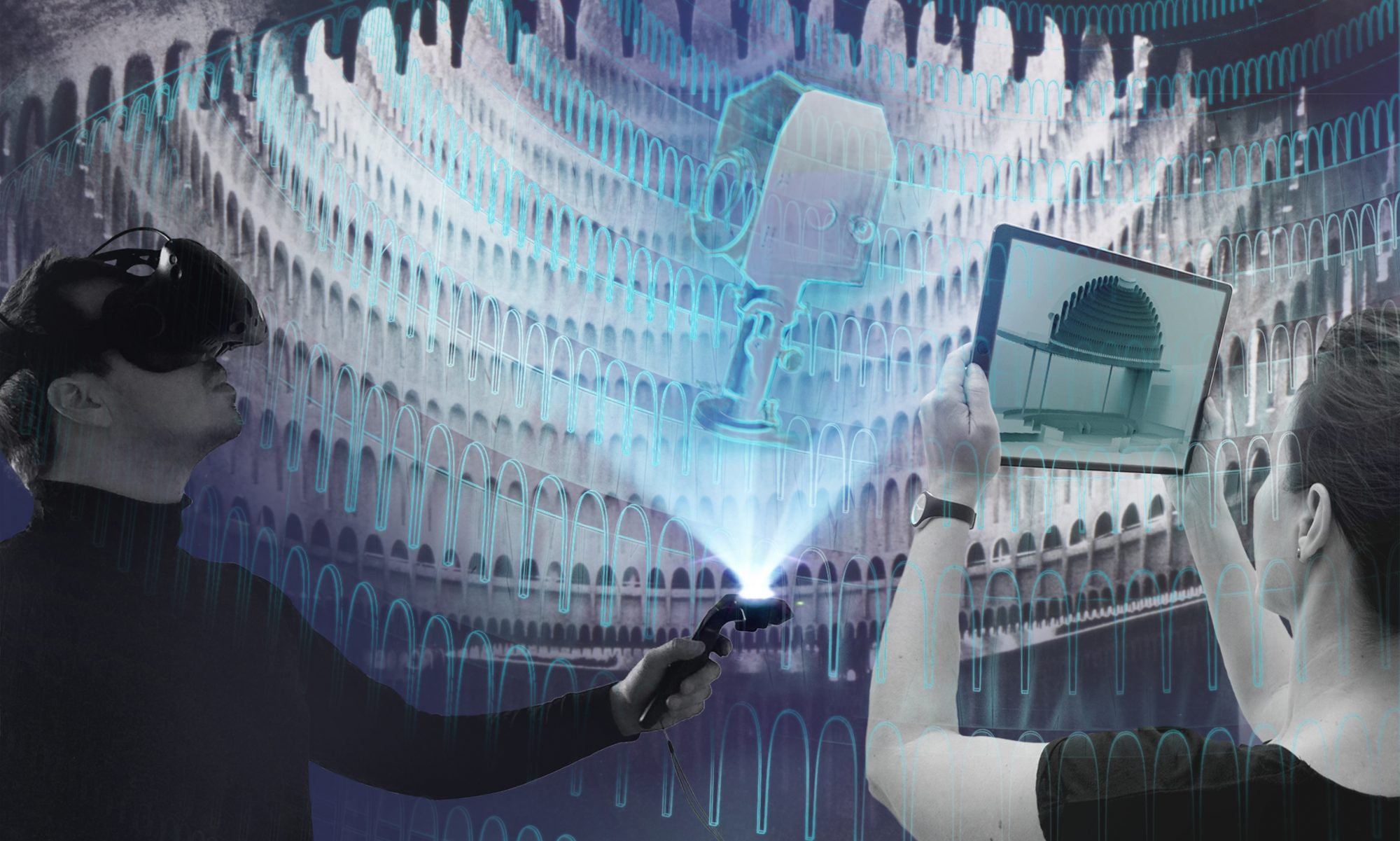

In the conception of digital experiences in virtual reality, all these forms of participation are part of the repertoire. The blending of real spaces with virtual worlds and the encounter of human actors with AI-controlled NPCs create new, inexhaustible possibilities for interaction and creative freedom. (NPCs – or non-player characters – are characters in a game that are not controlled by human players. The term includes actors in the action as well as extras.) Forms of active audience participation increase the degree of immersion and the intensity of the experience, resulting in a stronger identification with the characters and their role in the story. Activating the audience also means dismissing them as spectators and establishing them as actors – in other words, turning them from receiving audiences into performing protagonists.

When the audience is integrated into an artistic performance through the use of participatory strategies, the suggested cooperation at eye level often takes place only superficially. The participants are only given limited power to act and are usually involved in the supposedly collective creative process without authorship. As an extension of participatory processes, co-creative processes are playing an increasingly important role, not only in the artistic field. Their aim is to create works in which all actors are directly involved in the creative process and simultaneously act as recipients, co-authors and editors of the work. Co-creation thus describes the method and the result of a joint creative process by heterogeneous groups of people or statuses. This kind of art process distributes authorship between artists and the audience, leads to a kind of de-hierarchisation and expands the role of the recipient in the „artist-artwork-viewer complex“.

The project examples examined so far do not exhaust this expanded space of possibilities in their mediation scenarios: The audience has hardly any influence on the progress of the stories, can at best move freely and retrieve content. This form of mono-directional communication – a classic sender-receiver constellation – makes sense in terms of a number of aspects and is desirable in certain performance contexts. For example, the precise control over the dramaturgical sequence, the directed viewer gaze, and the framing of the field of vision lead to a clear artistic setting and high quality of experience. The reduced use of interaction and freedom of movement allows, for example, the omission of external input devices and thus a maintenance-friendly technical setup.

From the audience’s point of view, this means above all simplified operability and easier accessibility, since no complex controller assignments have to be learned and interfaces operated. However, forms of active audience participation increase the degree of immersion and the intensity of the experience, resulting in a stronger identification with the characters and their role in the story. Activating the audience also means “abolishing” them as spectators and establishing them as actors – that is, turning them from a receiving audience into acting actors.

A simple form of influencing the plot of a pre-produced work has its origins in the game books of the 1970s and 80s: at the end of a book chapter, the readers have various options for the continuation of the plot. Depending on the decision made, the story continues at a different point in the book, thus creating a series of different – but limited in number and predefined – storylines. This form of influence can be found in many video games and interactive movies. The special episode Bandersnatch of the series Black Mirror is an example worth highlighting, because the storytelling method is not only used here, but is itself made a theme as “pretended freedom of choice.” The possibilities of this storytelling method are also explored in theater: In the first episode of the three-part mixed reality series Solo, author Sebastian Klauke and the Staatstheater Augsburg use this game mechanism and let the spectators become active investigators in a VR world. The VR viewer solves an interactive criminal case; the viewers control the course of the approximately 45-minute plot by making decisions during the investigation and the interrogation of witnesses and suspects.

The theater collective Makropol experiments with a variation of this narrative in the production A Taste of Hunger. In this VR experience – described by director Christoffer Boe as a “narrative soaked in quantum physics” – space and time seem distorted. By actively observing, one becomes the creator:in of an individualized experience, because with every step the viewer:in takes, the environment, the scene, and the characters change. The space is used here as an interface: Volumetric video sequences are triggered by the movement of the active viewer:in. (Volumetric video is a technique that uses multiple cameras to capture a three-dimensional space or performance.) This simple interaction mechanism allows for a complex experience and creates a strong narrative and spatial impact.

A similar mode of physical influence – extended by a reacting artificial intelligence – is used by the VR experience Das Totale Tanz Theater. The project was created on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus in 2019 – under the auspices of the Interactive Media Foundation, choreographed by Richard Siegal with music by Einstürzende Neubauten, the design of the scenography and costumes as well as the technical implementation were provided by the experts from Artifical Rome. The dramaturgy is carried by the electronic music of the composer Lorenzo Bianchi Hoesch. Inspired by Oskar Schlemmer’s stage experiments and Walter Gropius’ ideas on total theater, the question is asked: “Who exerts influence and who controls whom?” In the interactive production, visitors:inside immerse themselves in a virtual stage space via VR glasses and experience a dance influenced by their own movement in real time. Choreographer Richard Siegal has developed an instrumentarium of movement sequences for the digital dance robots, which are constantly recombined and assembled by an artificial intelligence trained by him. The interlocking of man-made choreography, personal intervention, and machine algorithms results in ever new forms of movement and dance in space. Together with the activated “dance machine” it is necessary to go through a choreography, accompanied by the question of the real possibilities of influence on the surrounding space and on the algorithm.

Taking it a step further, The Under Presents by Tender Claws combines virtual reality, gaming and theater in an unconventional way. The story is set between two worlds: a surreal bar with a vaudeville stage and a capsized ship (the titular “Under”). Here you follow the interlinked fates of the characters, there are explorations, puzzles and narrative elements. The mysterious survival story takes place in a time anomaly – as a player:in, you can turn time forward and backward to influence the fate of the characters – nothing in this game follows a predictable plot. The game mechanics work in both single-player and multiplayer modes. What makes it special, however, is that (at certain times) real actors:inside intervene live in the action. The members of the New York ensemble “Pie Hole” developed their own VR shows for this, which are performed on the variety stage. However, they also interact spontaneously with the users and entice them to behave in a certain way within the story. The nesting of single, multi- and live elements results in an individualized experience with great freedom of choice for the users.

From the point of view of shared experience and the greatest possible scope for agency, it is worth taking a look in the direction of collaborative design programs. Based on the source code of the VR painting program Tilt Brush developed by Google, the drawing program Multibrush enables collaborative work in a virtual space. Since the connection is established via the Internet, several users can log in with their VR goggles, participate simultaneously from different locations, and thus give free rein to their creativity together. Within a shared virtual environment, three-dimensional graphics and sculptures are drawn in space. Since there are no tasks and specifications through the program, the results are open and are democratically (and sometimes chaotically) negotiated among the participants. A co-creative process takes place without external guidelines or structures, which allows an “artistic” work to emerge from the community.

The observation of these project examples raises questions about the creative sovereignty and authorship of artistic processes, about the potentials and limits of co-creative ways of working. How can this potential of activated audiences and co-creative work be used to create an artistic experience?

Read more in our blog article about cocreative encounters in hybrid real stage spaces.

Authors: Franziska Ritter and Pablo Dornhege

Further reading:

Siegmund, Gerald The Problem of Participation: https://www.goethe.de/de/kul/tut/gen/tan/20708712.html, 2016

Simón Lobos Hinojosa & Charlotte Rosengarth: https://www.uni-hildesheim.de/kulturpraxis/partizipative-kuenste-im-rahmen-kultureller-bildung