What dramaturgical and scenographic means do we use to design virtual experience spaces? How can a room be set in motion virtually? And how do visitors immerse themselves in such a moving space?

“There, backstage centre right, that’s where I liked to stand before it started.” In the middle of the backstage, halfway up, hangs a massive, mirrored, spinning apparatus that resembles an oversized drill head. Behind that, we see the round horizon, the curved backstage wall on which miraculous clouds glide along and make their circles. “The rattling of the cloud machine … yes, that was its real name: cloud machine. It just produced clouds … but what clouds!” Our gaze wanders from the round horizon towards the backstage, where we can observe from a distance the hustle and bustle of extras, make-up artists and a group of dancers. “Hearing the clouds rattling and looking at the hustle and bustle backstage … that always calmed me down.”

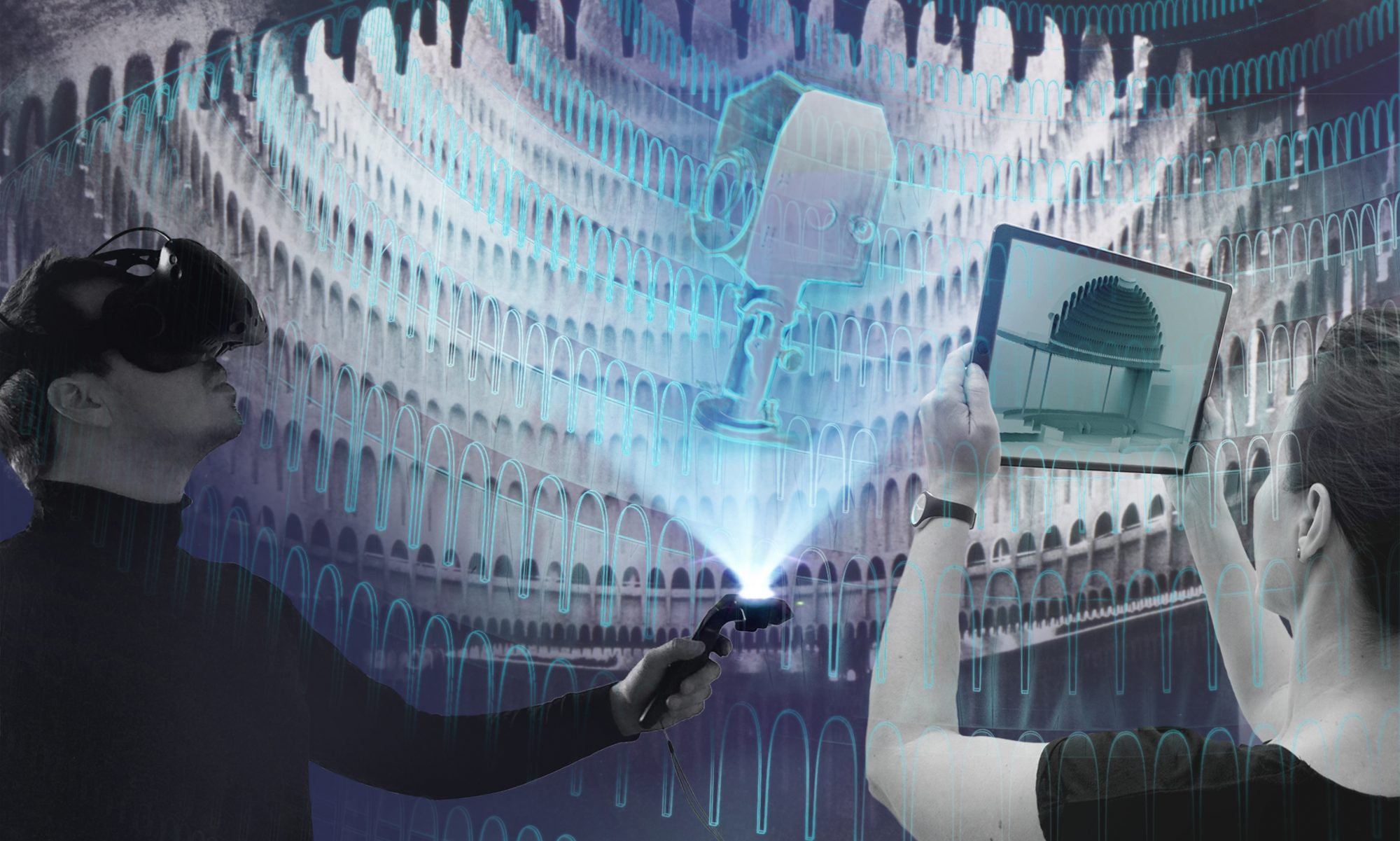

This excerpt from the script for the VR production „Opening Night at the Große Schauspielhaus Berlin” takes us into the emotional world of the young lighting technician Otto Kempowski. You feel for him when he stands on the lighting bridge for the first time on 23 December 1927 and the opening curtain opens for the celebrated singer Fritzi Massary at the Große Schauspielhaus Berlin. As a virtual companion, you follow Otto Kempowski for ten minutes through the impressive building. It is the premiere night of the operetta “Madame Pompadour” and the theatre shows its exciting, vibrant side. So before the red velvet curtain rises, Otto takes us behind the scenes and shows us en passant his everyday working life: from the lonely cigarette at the stage door in the bone-chilling December cold, to the damp and cheerful walk through the smoke-filled canteen, to the side stage where other technicians are frantically making final touches to the spotlights. Individual, coordinated spatial images are strung together – like in a kind of exhibition production or a play – some of them alternating, others building on each other. The collage-like spatial images are linked dramaturgically and scenically to form a multi-layered overall experience. Thus we look through a digital window of experience into the past, in which the history of the theatre, its architecture and its art can be experienced spatially. This type of guided, linear narrative dramaturgy contrasts with other non-linear dramaturgies, such as in the VR experience The Colosseum District by Rome Reborn, which also deals with virtually reconstructed historical architecture. In the reconstructed ancient Rome, VR users can move freely back and forth between different monuments in “exploratory mode,” teleporting from place to place and determining their own length of stay. (In the context of computer games, an “exploratory mode” describes the ability of players to freely explore the game world, rather than being guided from place to place by a dramaturgy dictated by the game.) The two projects are also diametrically opposed in the way they are addressed and didactically prepared: While in the virtual Große Schauspielhaus the theater visitors are literally taken by the hand by protagonists in order to go on an emotional journey down memory lane, in The Colosseum District historical knowledge is conveyed through spoken expert commentary. This objective approach is complemented by text panels with factual information about the buildings.

The VR project Home After War, directed by Gayatri Parameswaran and “filmed” in Iraq in 2018, takes a different approach. It tells the tragic real-life story of a fled Iraqi family returning to their hometown after the end of the war. Family father Ahmaied Hamad Khalaf invites people to enter his house with him, which still shows the traces of the war and where booby traps might be lurking. In this project, too, visitors can move freely and self-determined through the building. The sequence of rooms is determined by the architecture of the building and not by a scenographic design or dramaturgical setting. Through the photogrammetric recording and realistic reconstruction of the still existing building with all its traces of destruction and personal legacies, strong spaces of memory are created. Through Ahmaied’s narrative, the user experiences what it is like to fear the home one once loved. His way of direct personal address creates an emotionalized access and leads to an emphatic approach to the difficult to convey topics of trauma and loss. Through the way the characters are led and the emotionalization – similar to the Virtual Große Schauspielhaus – distance is reduced and a special closeness to the story is created.

Another possible approach is shown by the mixed reality installation Schumann VR by the agency A4VR with a journey back in time to the year 1852, in which the user assumes the role of the main character Robert Schumann. In the first-person perspective, the VR users go on a biographical search for clues in historic Düsseldorf and witness Robert and Clara Schumann’s musical work. The protagonists are recorded with motion capture, 3D scans and volumetric capturing, plus exact photogrammetric reproductions of artifacts. The city has been reconstructed with the help of city maps, engravings and old photos in cooperation with historians – in this way, music history is made tangible.

The comparative projects shown use different but singular narrative perspectives and thus paint a certain mono-perspective picture of musical, urban or contemporary history. In order to make it possible to experience theater heritage and theater-historical knowledge in all its facets – as an architectural and as a thematic space – we approach the theater from three different directions in the VR project An Evening at the Großes Schauspielhaus: in addition to the aforementioned narrative thread of the stage technician Otto Kempowski, the user:inside has the option of either accompanying the theater visitor Walter Schatz through the impressive foyers into the auditorium, or to join the singer Fritzi Massary through the stage entrance into her dressing room and finally to stand at the edge of the stage in front of 3. 000 spectators. The necessity to choose between different protagonists at the beginning of the experience leads to different approaches to the theater building in terms of content and architecture: the view of the theater guest Walter Schatz conveys to us the socio-political tension in the Weimar Republic, which was shaken by the economic crisis; the aging diva Fritzi Massary, on the other hand, gives us insight into the emotional world of a world star and lets us participate in her self-doubt after harsh newspaper reviews. This gives the user:inside the opportunity to literally take a stance themselves and view the building in its social context from their own perspective.

The same approach of illuminating a certain motif from different positions and through different characters is used by the VR experience One City – Two Worlds by the company Timeride Berlin. After an introductory exhibition in which the theme of the divided city is presented, the visitor:inside enters a cinema-like room in which three very different, fictional personalities introduce themselves in a trailer and invite the visitor to a city tour through the divided Berlin of the 1980s: the rebellious craftsman, the reflective architect or the maladjusted border crosser from the West. The virtual staging then actually takes place as a joint VR bus trip through East and West Berlin: visually the same for everyone, but the ten-minute trip is commented on and contextualized by the different audio tracks of the chosen protagonist:s from different perspectives. This mediation strategy leads to an activated audience that is encouraged to discuss and reflect on the different ways of looking at things through the shared temporal-spatial experience of the different storylines. The polyphony of the narrative results in a multi-perspective view of city history, individual buildings or fates, and a lively, plural image emerges that is emotionalized by the three individual stories.

An emotional charge is also evident in the virtual Großes Schauspielhaus: even though it is primarily the protagonists Otto, Walter and Fritzi who have their say here, the actual main actor is the building itself. Through the voices of the three characters, we make it speak and make it the secret “hero” of the story. In this way, Hans Poelzig’s unique architecture becomes a space of knowledge that is expanded through the spatial contextualization of the individual stories. In addition, the targeted linguistic highlighting of architectural elements, spatial situations and objects directs the VR user:s gaze and creates further offers of knowledge.

The Großes Schauspielhaus is a space that we know today only from photographs. Our image memory is limited to single, specific architectural motifs and spatial situations that, without context, create a highly reduced image of the theater building; from these singular and static positions, the complex spatial contexts are not revealed. In order to develop an understanding of a spatial body in its three-dimensionality, movement and thus a change in the relationship between the object and the person viewing it is required. This movement is indispensable in virtual space, because it is only through this dynamic that the image of space develops into an effective pictorial space. In the VR experience, the virtual theater visitors are moved through the Großes Schauspielhaus as if on rails: the direction of movement is predetermined, but there are no forced camera pans or zooms – the visitors can let their gaze wander freely. Protagonist Walter Schatz asks them: “Look up! These huge columns hanging from the ceiling – like in a stalactite cave! […] That was pretty daring for the year 1927, don’t you think? And if I remember correctly, there were lights in the dome showing real constellations.”

This linear-narrative method of guided viewing is supported above all by scenographic means of design. A cinematic lighting design that goes beyond technical illumination emphasizes architecturally significant areas and directs the user’s gaze. A spatially immersive sound design gives a sense of the dimension, materiality and atmosphere of the different spaces. From time to time situations are condensed by an artificial fog and concentrated on the surrounding field of vision, sometimes the fog clears and opens up new vistas. The visual reconstruction of the architecture does not attempt a naturalistic recreation of the original materialities. Buildings and objects are instead textured with a paper-like surface, creating associations with Poelzig’s hand-drawn design sketches. Following this sketchy style, the protagonists and supporting actors are drawn as two-dimensional “stand-ups” and are reminiscent of book illustrations from the 1920s due to their quick and contoured penwork. The visual proximity to graphic novels corresponds with the use of other comic stylistic devices. Written comments by critics appear in the dressing room mirror, press comments float as oversized texts in the stage space, and at the end the visitors fly weightlessly through the applause-filled auditorium. The creative liberties do not break the inherent logic of the story, but lead to a special atmosphere and promote immersion in the story.

The process of immersion – subsumed under the term immersion – is one of the main characteristics of virtual reality and contains special potentials. In their book Patterns in Game Design (2004), Staffan Björk and Jussi Holopainen describe four different forms of immersion: spatial, emotional, cognitive, and sensory-motor immersion. Spatial immersion arises from the visual quality of the experience and determines the willingness of the recipient to accept the artificiality of the virtual world as natural. Emotional immersion becomes possible when a narrative content leads to emotional arousal and thus absorption by the story (Zhang 2017) – it is thus similar to the effect of an exciting read or a gripping play. Cognitive immersion is based on focused abstract and creative thinking and is usually achieved by solving complex or creative tasks. Sensory-motor immersion is the result of feedback loops between the user:s physical actions and their effects on the (play) event, where the perception of one’s physical existence can shift from the physical environment to the simulated environment.

In the VR project Opening Night at the Großen Schauspielhaus – Berlin 1927, we combine the use of narrative and scenographic means to create presence, two methods that have always been familiar from theater: gripping narratives create emotional immersion, while an atmospheric and consistent scenographic design contributes to spatial immersion. To create a plausible, i.e., a “believable” imaginative space, a realistic spatial representation is not mandatory. A sense of presence and immersion can be created in a virtual stage space equally with a high degree of visual and acoustic elaboration or, as we point out in the blog article “Cocreative encounters in hybrid-real stage spaces”, can already be achieved with minimal and abstract design means.

The scenographic design, the narrative style and the mediation strategy are determined by different factors: the target audience, the existing knowledge and data base, the historical or cultural relevance and characteristics of the subject, but also one’s own artistic and creative attitude. In short: The “how” results from the question underlying each design: To whom do we want to tell what and why?

Authors: Franziska Ritter and Pablo Dornhege

_________________

Björk, Staffan and Holopainen, Jussi: Patterns In Game Design. Charles River Media. S.206, 2004

Zhang, Chenyan & Perkis, Andrew & Arndt, Sebastian: Spatial Immersion versus Emotional Immersion, Which is More Immersive? 2017