Lectures by Franziska Ritter, Pablo Dornhege (digital.DTHG) and Maren Demant (Invisible Room), summarized by Kai Schnier, kultur-b-digital.de

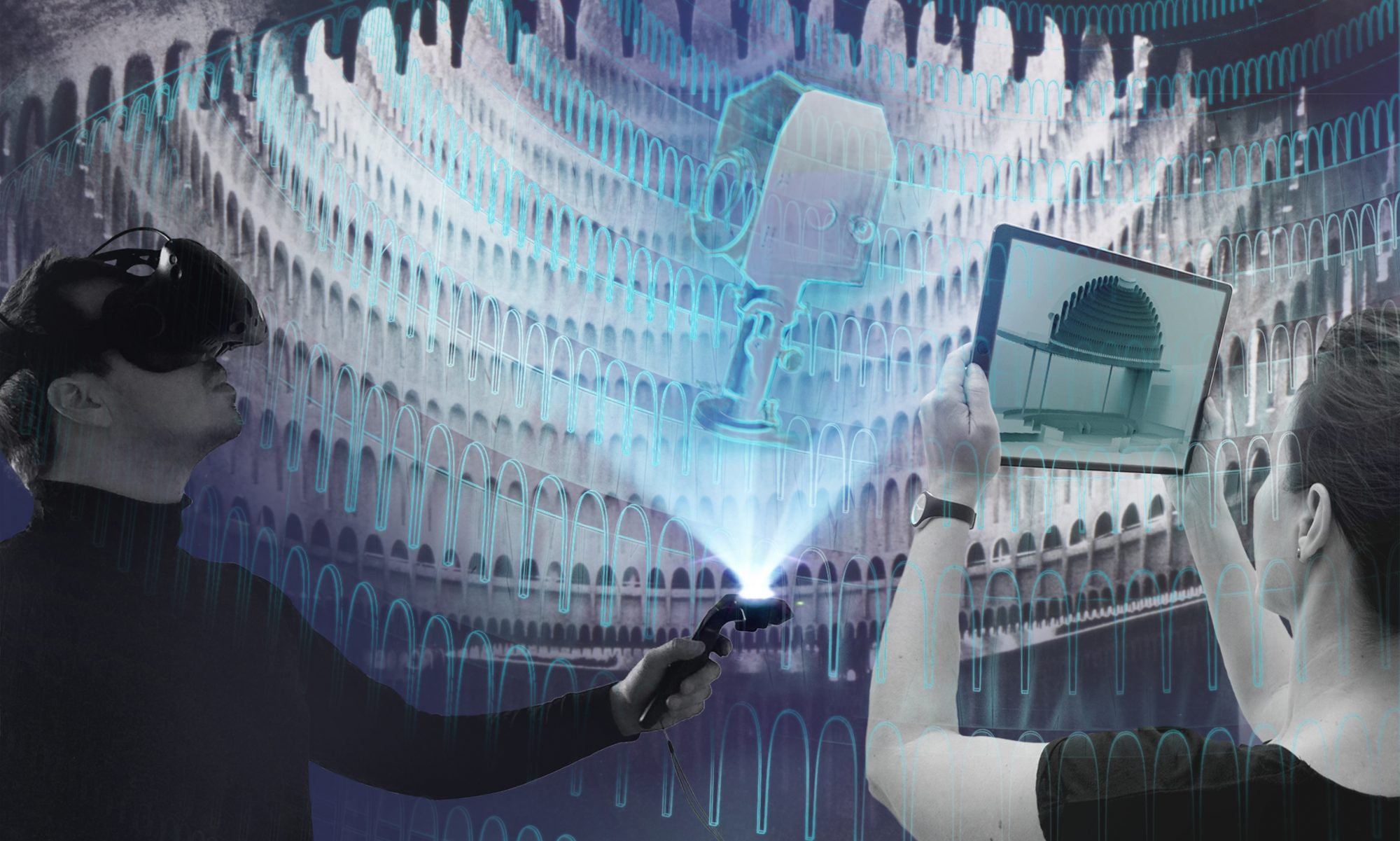

Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, Mixed Reality: not only in the tech industry, but also in the cultural sector, these have been the new trend terms for quite some time. Wherever technology can be used to improve the visitor’s interior experience or simply to make it more exciting – for example through VR glasses in museums – cultural institutions want to be at the forefront. In this context, the understanding of the differences between Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Mixed Reality has often not yet grown. So what actually distinguishes VR and AR? What can technology for cultural institutions realistically achieve so far? And what can it not yet do?

These questions – and the appropriate answers – were the focus of the event “Im/material Spaces – Virtual and Augmented Reality open up new approaches to cultural heritage”, which took place on 26 November 2019 at the invitation of and in the rooms of the Technology Foundation Berlin with the speakers Franziska Ritter and Pablo Dornhege (both research and teach at several universities and jointly head the research project Im/material Theatre Spaces) and Maren Demant (XR designer and founder of Invisible Room).

In his lecture on the basics of Virtual and Augmented Reality, Pablo Dornhege explained the essence of Virtual and Augmented Reality with the help of a glossary of terms and showed possible ways of dealing with the technologies in a media-compatible way. The following guide summarizes the most important basics of all the speakers’ contributions:

AR + VR in cultural institutions – a guide

The history of immersive technologies

Immersive technologies have not only emerged in recent years, but have been part of the repertoire of art, culture and science for centuries. Even the early baroque theater, with its deep perspective stage design, simulated an expanded spatial reality that was created solely in the minds of the viewers. Similar examples can be found again and again in the history of mankind: For example, artists of the Romantic period attempted to offer viewers a 360-degree impression of certain scenes with huge panorama paintings.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Emperor’s Panorama enabled up to 25 people to “virtually travel” to distant places at the same time with automatically changing stereoscopic series of images.

In 1954, producer and cameraman Morton Heilig developed the Sensorama, which was to offer the first fully immersive cinema experience. Heilig experimented with a device that not only showed moving pictures but also emitted smells that matched the scenes.

More advanced in 1968 was the “Sword of Damocles”, developed by computer technician Ivan Sutherland, which is generally regarded as the first Head-Mounted Display (HMD). It was already capable of fading digital images into the viewer’s field of vision, thus creating a hybrid of digital and analogue space. In the mid-1970s, computer artists* like Myron Krueger were already experimenting with the term “artificial reality”. Krueger’s Artificial Reality experimental laboratory called “Videoplace” at the University of Connecticut made it possible to interact with a computer-generated artificial reality by moving one’s own body.

Modern forerunners of today’s VR glasses were created in the mid-1980s and early 1990s in the development laboratories of NASA, which used them to prepare astronauts for use in space. The first commercially available VR systems, or virtual reality helmets, were the Forte VFX1 headgear in 1994. The mass-market 3D graphics cards that came onto the market shortly afterwards accelerated this development even further.

However, the foundation for the current hype about immersive technologies and VR in particular was then laid by the iPhone: With the high-resolution display of modern smartphones and the built-in tilt and acceleration sensors, the foundation for a quantum leap in new virtual reality systems, such as the Oculus Rift, was finally laid.

Since virtual reality has become a concept and immersive technologies can also be purchased by normal consumers* in retail stores, there is pure chaos around the exact terminology of artificial reality. It should generally be mentioned that the most well-known terms – Virtual Reality, Mixed Reality and Augmented Reality – all serve to describe certain gradations of the virtualisation of reality:

Virtual Reality (VR) is at one end of the spectrum: it describes the fully immersive simulation of physical space, i.e. the complete immersion in a virtual environment that is perceived as real. In its most perfect form, VR is indistinguishable from the physical manifestation of reality for viewers. Interactive worlds of experience in which users can immerse themselves with virtual reality glasses are an example of VR.

In contrast to VR, Augmented Reality (AR) “only” overlays the physical reality with digital content. It is thus located closer to the reality end of the spectrum. One example of the use of AR are applications in museums, in which visitors* can film a painting on the wall using an iPad, over which several new digital layers, such as earlier sketches of the work, are simultaneously superimposed on the device screen.

In so-called Augmented Virtuality, the real world is not enriched by digital layers, but the digital world is augmented by physical space. This is the case, for example, when the perception of a virtual space is supported by physical factors. For example, if a user sees images of a campfire and a heating lamp simulates the heat emitted by the fire, this is a form of augmented virtuality.

Terminal devices for the representation of virtual worlds

In order to make VR and AR experiences tangible, there is a whole range of terminal devices available so far. AR can already be experienced via smartphones, tablets and smart glasses. There are three different methods for anchoring digital elements in real space:

- Marker-based systems, in which a picture is taken by a camera and its contrast points are automatically recognized and analyzed by the software

- Markerless systems, in which – as in the case of the IKEA home planner, for example – 3D objects are extracted from a database and inserted into a digital representation of the room. Here the position of the digital objects is defined by the application, not by a marker.

- Location-based systems in which virtual objects become visible at predetermined locations (for example, by using a smartphone with GPS positioning).

Even mobile VR systems such as VR glasses and VR headsets are by far not all the same. A distinction is usually made between so-called 3DOF and 6DOF systems, where “DOF” stands for “degrees of freedom”:

- In 3DOF systems such as the Oculus “Go” or Google Cardboard, the user* can look around, i.e. look up and down and tilt and turn his head, but cannot approach the digital objects because the system does not register his own position in space.

- With 6DOF systems such as the Oculus Rift or HTC Vive, in addition to the rotation of the perspective, movement in space is added to the rotation of the perspective. So you can not only approach virtual objects but also move around them.

Other differences also exist in the mobility and display quality of the respective devices. While wired VR headsets usually offer higher computing power and can play more complex applications, the freedom of movement is limited with these devices. With wireless systems, full freedom of movement is guaranteed, but the picture quality often suffers.

VR or AR in cultural institutions: What makes sense?

When developing VR and/or AR projects for cultural institutions, the question of what content should be conveyed using the technology should always be at the forefront. Instead of thinking in terms of technology, those responsible should first clarify why they want to use VR or AR at all.

When deciding on special VR glasses or other devices, the users should also be at the forefront. What are the possible fears of people who have never had contact with VR and AR? What is the best way to introduce beginners to the technology quickly and easily? And what circumstances must be given so that the AR and VR systems can develop their full effect? These questions should be considered when choosing the technology.

It is often underestimated how much practical hurdles can limit the successful use of AR and VR systems: Wearing comfort, compatibility with classic vision correction glasses and hygiene issues are often at the top of the list of concerns.

Not least because of unexpected difficulties such as these, it can be useful for cultural institutions to rely on additional support for VR and AR projects in addition to assistance with technological development. The presence of trained personnel can help many new users to overcome their fear of contact with technology.

In addition, cultural institutions can plan and implement VR and AR projects on a smaller scale in order to slowly gain experience with the implementation and introduce users to the new technology, for example in a museum context or in the theatre.

Opportunities and risks of VR and AR in cultural institutions

In the context of the work of cultural institutions, the use of VR and AR can offer both opportunities and risks. For example, immersive technologies in museum spaces have the potential to increase the visibility of exhibitions, open up new sensory and epistemological perspectives for visitors, and contextualize collection objects using digital information. In addition, VR and AR enable users to interact with historical objects for the first time and to perceive detailed information that would not be visible without technology – such as background details on exhibits that are digitally displayed.

At the same time, however, the arbitrary and ill-conceived use of VR and AR can also disrupt the content of an exhibition and, in case of doubt, overwhelm visitors. Especially if it has not been clarified beforehand why immersive technologies should be used and what purpose they should serve within the program – beyond the pure technological aha effect – at all. Not least for this reason, it should be clarified at an early stage what role VR and AR stations should play as an addition to the actual exhibits. Is it about making the real exhibits more visible? Should the physical format rather take a back seat? Or should the immersive technologies form a separate part of the exhibition? All these questions need to be answered in order to exploit the potential of VR and AR in the best possible way for your own purposes. In any case, it should also be considered that immersive technologies not only have a positive novelty value, but also, due to their short history within cultural institutions, sometimes have a certain disruptive effect: For example, by wearing VR glasses, visitors* may feel isolated from the rest of the audience or even react physically to the VR experience, for example with feelings of dizziness.

Opportunities:

- Increased accessibility

- Visibility of collections

- Motivation through technology

- Research opportunities

- New sensory and epistemological dimensions

- Enabling time travel

- Contextualization of collection objects

- Interaction with historical/original objects

- Emotional activation of the visitors

- Possible links between analogue vs digital

- Making the invisible visible

- Detailed information accessible via various filters

- Possibilities for multilingualism

- Inclusion

Risks:

- Arbitrariness can destroy an exhibit (art or similar) and content

- Where and when is AR/VR/MX really useful?

- does the physical format take a back seat?

- requires a lot of support, 1 to 1

- unattended continuous operation possible

- “Willingness” of the method?

- “Prohibition of overpowering” (Beutelsbacher Consensus)

- Distraction through technology / user guidance

- limited visibility area

- Group capacity? -> Separation

- Blockade through “artificial” contrast between analogue – digital / real – fake

- Storytelling + mediation are not considered enough in view of the technical possibilities

- AR with face recognition, privacy?

- partly still “too” artificial

During the event, VR and AR projects were presented at nine stations. This was 100% very well received by the participants*, as it offered a practical insight into the variety of technical possibilities.

Presented VR / AR projects

- Digitale Kunsthalle. ZDFkultur

Gerhard Richter, Auftragsbildnisse Source: „Virtuelles Laminat“, deichtorhallen.de - The Kremer Museum / 2018

VR Cube der Galerie Roehrs & Boetsch , Zürich - Museum4punkt0: AR in der Gemäldegalerie , Berlin

Torso von Belvedere , Hochschule Magdeburg & Winckelmann Museum Stendal, 2017 - Messengers of the AI , Dennis Rudolph, 2018

- KRIEGsgefangen. OHNMACHT. SEHNSUCHT. 1914 – 1921 /Deutsches Auswandererhaus, Bremerhaven

- VR Lab / Deutsches Museum Digital, München

- Abenteuer Bodenleben, Senckenberg Museum für Naturkunde Görlitz

- Jurameer, Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt

- The Dial, Flaherty Pictures & Nightlight Labs

VR Try Out Stationen:

- Wadi al Helo. Storytelling-based, virtual journey to Wadi al Helo, World Heritage Site of the United Arab Emirates Office for Cultural Heritage Sharjah, United

United Arab Emirates | American University Sharjah & Studio 105106 | 2018 - Hühnergott – digital.dthg & invisible room | 2019

- Das Städel Museum im 19. Jahrhundert. Virtual museum developed with scientists in 2016 | Reconstruction of the historical museum collection from the 19th century. Städel

- Anne Frank House. A trip to Anne Frank’s house to the Time of her diary entries. Force Field / Anne Frank Haus | 2016

- Hold the World. A virtual tour behind the scenes and into the collection of the Natural History Museum London. Sky UK Ltd. | 2018

AR Try Out Stationen:

- Interaktive Klangkarte. So klingt Berlin. Application that set the sound of Berlin to music by the Konzerthausorchester and transformed it into an interactive city map. APOLLO (Virtuelles Konzerthaus und HTW) | 2019

- Das virtuelle Quartett . First virtual string quartet worldwide. With the help of an application, four playing cards are interactively brought to life, each of which lets one or more quartet voices sound. APOLLO (Virtuelles Konzerthaus und HTW) | 2019

- Animalia Sum. Artistic work that describes a journey into the future and makes it possible to experience the effects of environmental conflicts and resource scarcity from the perspective of animals – Bianca Kennedy & The Swan Collective. | 2019

Further interesting links

- Museum4punkt0 Teilprojekte

- Museum4punkt0 Symposium 2019

- Museum4punkt0 Studie zu Möglichkeiten und Grenzen musealer Vermittlung mit VR

Literature / Articles

- VR im Museum

- Parallelwelten – VR in künstlerischen und musealen Kontexten

- VR-Experience Auschwitz: Die Banalisierung des Holocaust?

Blogs and Podcasts

- Virtuelle Narrative Räume

- Storytelling in VR

- Plattform und Datenbank für VR Kunst

- Podcast zu den Potentialen von XR, immersiven Storytelling…

Questions to

Pablo Dornhege: pablo.dornhege@dthg.de

Franziska Ritter: franziska.ritter@dthg.de

Maren Demant: info@invisibleroom.com

Fotos: Michael Scherer