Chris van Goethem, researcher and teacher for technical theatre and history at Erasmus University in Brussels at the RITCS School of Arts, started in the 80s as a stage manager with touring theatre companies. By now he is working in two different areas: on the one hand everything that has to do with competences, knowledge management, organising of education programs and structuring international exchanges. On the other hand researching the history of technical theatre. Why is that? He noticed when teaching, there was hardly anything written, and what was written was mostly written by non-technicians, that in a sideline of a book told something about technology. So bit by bit he started to find out that what they told him, sometimes just was impossible. So he started researching that.

Franziska: We are working together in the Erasmus+ CANON Project. What is this project about and why is it so important to work together at a European level about theatre history?

Chris: In fact we aim to have an overview of what happened in theatre history and what brought us to where we are now – in a European context. When you look at history from different points of the world, you see a different history. We just had our Erasmus-Meeting in Spain and got to know a lot about the very special and typical theatres of the Corrales de comedias, which is something we hardly know in Belgium – where we very well know Shakespeare, while all these things are related, but we don’t see how technology travels from one country to another, how it appeared, how it developed. So that’s why we use this Erasmus-Project with 8 university partners from 7 different European countries to look at it together, to take a critical dive at each others histories, see where the differences are but also where we have things in common (which is rather a lot), how one country influenced the other and so on. And that leads us to a “CANON of theatre technique history” – the most important elements in our history that every theatre technician should know, but also people from the outside should understand how we got where we are. The CANON Project has different sub projects like a huge open source Database (like a WIKI) serving as a platform connecting international knowledge, sources and collections; or different teaching methodologies like practical exercises, drawing methods or playful digital applications.

Franziska: Looking at the topic of digitization – not only during the pandemic THE buzzword in transforming education – which role plays digitality in your teaching process in your lessons at RITCS, what kind of tools are you using?

Chris: Well, you have to divide that into two parts: On the one hand all the equipment we are using is more and more digital. We came from analog, to electronic and now it’s more or less virtualized, so we don’t use physical equipment or physical controls anymore but virtual equipment as a software, running sound and light from the same computer for example. That’s the part, where our students are pretty familiar with.

On the other hand as teachers we are very much working from practice, not starting from theory classes, we do everything in the studio, at the theatre space, on the floor. And based on that we look at theory. Because what we saw is that it’s very important for students to have context and to understand how it works. Most of the context we give them is physical – but that’s also a limitation we have in our school, because if you are talking about light you can only work with 3 students in one physical space, otherwise you start influencing each other. And I think there, the virtual can do way more. The only doubt I have is that I don’t think people can make an interpretation of the virtual world if they haven’t seen the real world. If you have never seen how light could be manipulated in the real world it’s very hard to make an interpretation of a visualisation of light in 3D renderings etc.

In my own classes about history I mainly use a lot of videos, like short clips to support what I am telling. And a lot of visuals but mostly on a sketch level because I don’t have the possibility to prepare them in a more sophisticated way.

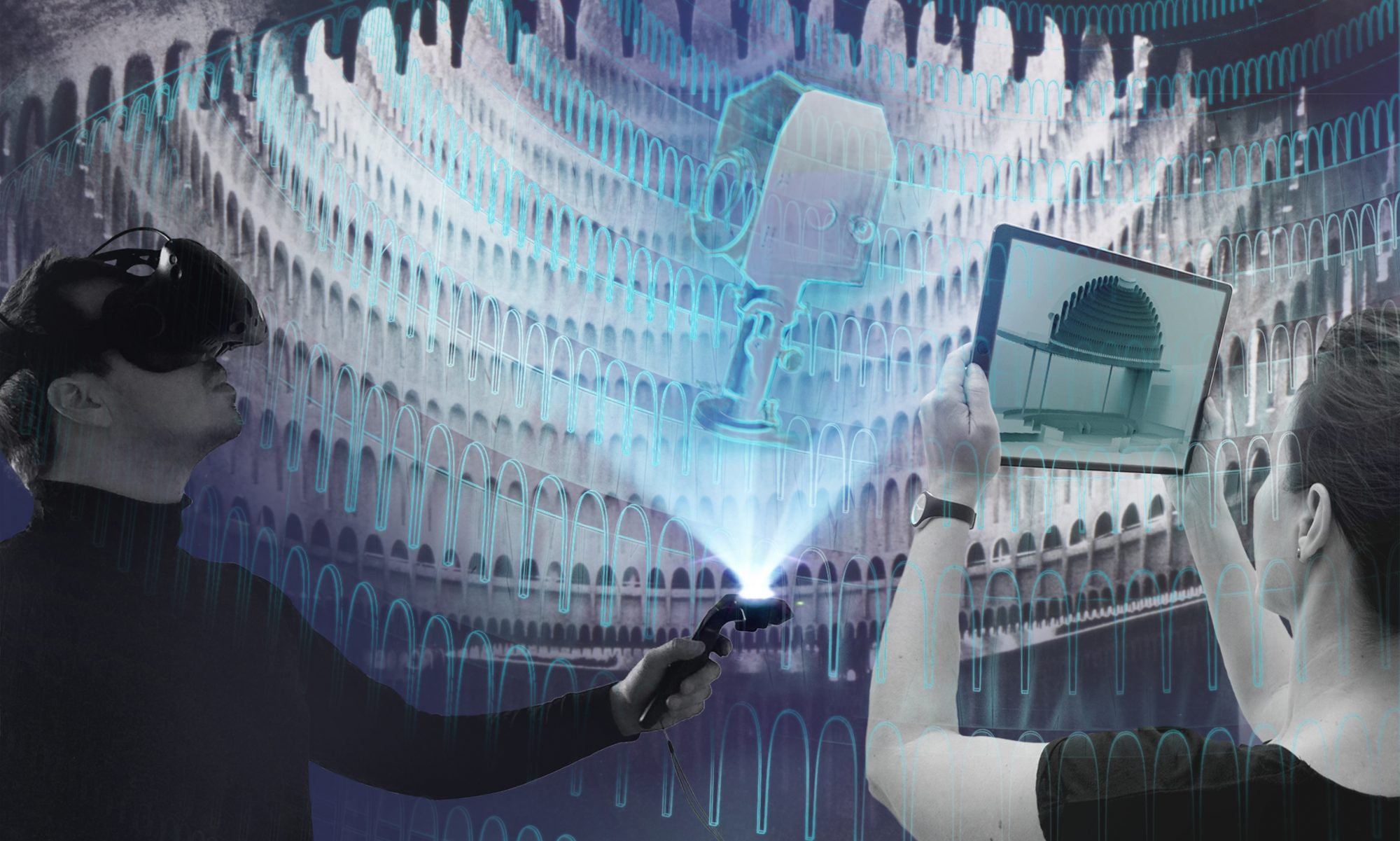

Franziska: The Web-XR-Prototyp, we developed for the CANON Project, would give you as a teacher and the students the possibility to connect the timeline with the database and act between analog and digital representation – like a presentation tool for three dimensional data. How do you evaluate the potentials of this?

Chris: The most important thing is that you don’t have to describe what a machine does, you can just show it. Students are more and more visual oriented, so the moment where you can see something in action it becomes clearer. For example it is very hard to explain how an under machinery works, but the moment you see it moving it becomes very evident. That’s a nice example, because if you are in a theatre house you will never be able to see the stage and the under stage and the upper stage at the same time – in a virtual model you can do that, you can also show what is happening also behind the walls. So for a thing like that it’s extremely useful. So I guess the most important thing we would use it for is for movement, how the mechanics works. For this application, visualisation tools work very well.

Franziska: When we developed the tool, we also had in mind that you can use the tool not only in your classroom or your theatre lab, but wherever and whenever you want. So that makes you independent from time and space. How important is this aspect?

Chris: Yes, that’s connected to what we see more and more. Students are learning based on need. And that need is not related to a class room, to a specific moment or a specific course. They are working somewhere or they are taking the bus and they want to look up something – and it should be available! And in that sense it’s different from our traditional way of teaching where you start with the Romans and where you end today. But in reality when you are in a theatre and you discover something or you have an idea and you want to figure out how it works, you need the information on the spot. So you’re not anymore talking about linear learning but you are talking more about knowing where to find stuff.

Franziska: By developing those digital tools, what do you think is the biggest challenge?

Chris: It’s extremely time-consuming and technologically it’s quite a complex issue. And I think there is no School in Europe that can afford to develop all these tools themselves – there it is absolutely necessary to do something on the European level. Be it that you develop things together or at least that we create a kind of standard to distribute it. Because it would be a shame to spend so much time and then not be able to use it in another place. And a second thing is: we have to find a way to make it open source in the sense that we all invest a little bit in these things and we share them then we create way more than if we all would work on our little island.

Franziska: In 10 years – how would you imagine your teaching in future?

Chris: I think it’s far more than my teaching, it is how teaching will work in general. My ideal is that you are starting in school – because you need a foundation – and then you swap between practice and school and more and more you have practice and less school. But you continue learning for the rest of your life. That’s one of the concepts we developed in another project, we call it a “structured portfolio”, where you just gather information of all your learning moments, where you set apart like “I want to learn this” and then you get some targets and then you get some learning content and you can do that on the bus or you can go to a course or you can go and work somewhere for a training for a couple of days. And that this whole learning part from the moment you get into professional education until the moment you retire and probably later you have one system that guides you through learning. And in fact at that moment we go back to the first universities where there was no management or professors organising the university but where students were asking experts to come and talk to them about subjects. I think that in a digital way that would be perfectly possible: You decide what you’re doing, what you want to do, where your fascination is and you’ll learn based on that.

Franziska: Anything you would like to share with us?

Chris: For me in fact the most important but also difficult thing is to get people to work together. If I go back to what we do with the database for example, ideally that will become a research tool that is used by a lot of people that all bring in their knowledge, so you create a common knowledge base. But people seem to be very scared – for all kinds of different reasons: mostly they think it’s because the others will know more than I do. Or they think they are not so good in comparison with their colleagues. Which is in fact against the whole logic of the freedom of research. The essence of the freedom of research is that you are allowed to fail. So creating this cooperation is the most difficult thing. The digital tools for it are just a reflection on the fact that we want to work together. I think that’s the essential.