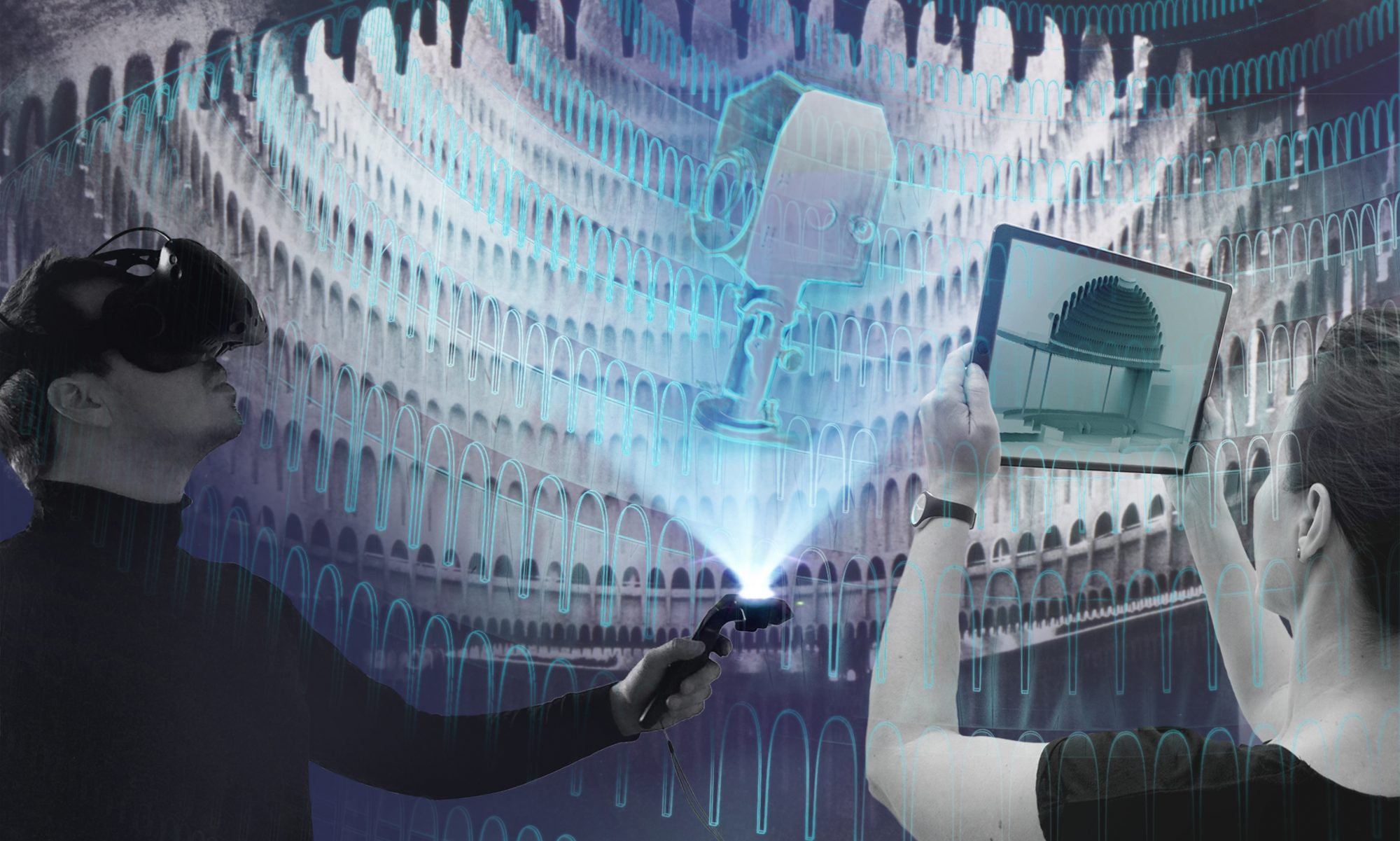

Project lead Franziska Ritter talks to Alexander Segin, Head of Event Technology Konzerthaus Berlin. During the 2020/21 season, which marked the concert hall’s 200-year anniversary, we had a chance to test workflows for virtual construction rehearsals with him and his team.

To what extent do you run construction rehearsals (Bauprobe) as part of your regular concert activities and why do you think it is useful to support them with digital tools?

We host nearly 500 events every year. Usually, we only do construction rehearsals for a few scenic productions a year. But these „Bauproben“ are much more „marked” than those done at theatres or opera houses because, with our stage being used so frequently for rehearsals, concerts and occasions where we rent out our hall, we are always on a tight schedule. We already knew from the beginning that the „Freischütz” (Englisch: The Marksman) productions we had planned for our anniversary year of 2020/21 would pose a great challenge regarding space and technology.

Can you describe these challenges using an example? And can you tell us how you handled them?

We were trying something new when we planned to restage Carl Maria von Weber’s „Der Freischütz“ with the Catalan theatre group La Fura dels Baus. We wanted to use the hall as an illusionary space. This meant that our approach and implementation were completely different from a normal concert situation. The hall’s 14 chandeliers were covered in fabric, and we planned an elaborate PreRigg construction for the different projection levels. We were faced with a very elaborate production that included a crane construction for artistry that made it necessary to plan out every centimetre. Our planning process constantly had to be adapted, not only because of the pandemic. In the end, we had to premiere it as an elaborate TV production without a live audience. This way, we could use the entire space, place the orchestra inside the hall and open different performance spaces for the choir, for example in the seating area. This meant we had to constantly change our plan; technically, we would have needed five construction rehearsals to reproduce everything.

How did the Virtual Bauprobe help you and how did you go about it?

We were working on an international production and several lockdowns prevented us from travelling and meeting up, so we had no choice but to establish digital ways of collaborating. Normally, a 2D plan in AutoCAD is sufficient for our scenarios. But in this case, because of the complexity of the design and our requirements for precision, we knew that working with 3D would be best. So, we worked on refining our blueprint, also using external help from Johannes Fried and Vincent Kaufmann from the digital.DTHG team.

I‘m sure the data basis was excellent because of your cooperation with Berlin‘s University of Applied Sciences (HTW Berlin) as part of the project „Virtual Konzerthaus“. How did you utilise that data?

We had already created a 3D view of our location as part of another project with the HTW university. This textured building model helped us create the first visualisations when we began planning the “Freischütz” project. But this type of model focuses on visual quality, which did not help us as technicians, especially when it came to avoiding collisions.

Therefore, we had to redesign our very precise 2D drawings and transfer them into the three-dimensional space so that we could create an accurate „image“ of the building structure. Luckily, we could use the textures from existing 3D models and project them onto the new geometry. So, the data has gone through a large development over the past two years – and so have we (laughs).

Does this mean that, from that point on, you activated a VR-ready 3D model? How did you use this model?

I used it internally to keep my team updated on the current status of the Rigg construction. We used the platform Mozilla Hubs to bring together the digital building model and the digital stage design and we made the different variants and technical solutions accessible in 3D. As we approached the premiere date, we used this online space to meet up with the artistic team. In the two weeks before the premiere, we met up almost twice a week.

Do you discuss this with other institutions, venues or colleagues?

There is a small network of institutions that work with digital projects like this one. That is why I think the more we all push this, the more podium discussions will be, the more we will be able to talk about it and eventually, we will no longer be in a niche of event technology. We are still at the beginning; task forces have yet to be formed. There is no standardisation in this field and workflows have not yet been defined. We are navigating an experimental field, which is still finding its form so that everyone can see its value.

The pioneer work that you are doing must require a lot of time and energy. What are the reactions in your team like, is there a lot of resistance? Following a trial-and-error approach can‘t always be easy.

I would not call it resistance, it is more a matter of ressort, which is understandable. Who is doing what, which department is responsible? We don‘t have a construction department that creates plans. I can‘t go to them and say, “This VR thing could take up about 10% of your work time.” A healthy amount of scepticism is necessary and normal when looking in a project like this. We need to ask ourselves: What is the value that this creates, now or in 10 years? We often hear things like, “We don‘t need this. This only creates more work for us. Don‘t we have enough to do already? We never used to do it this way!” At the same time, event technology is seeing constant development in the digital field and this is progressing faster than ever.

But isn’t “digital” actually a professional field in its own right at theatres? We can’t really expect everyone to go along with it on top of everything else.

We are currently learning in our digital projects what it takes, what we need and what needs to be considered. In my day-to-day work, I often don’t have the time to focus on new technologies, read articles or attend conferences. We will need to make the decision to hire specialists and pay them to help us. We would never have been this successful with our Virtual Bauprobe if we hadn’t had digital.DTHG to help us. You kept coming up with new ideas, showed us new software and tools and motivated us to go down a new path. This type of project support is almost like a department of its own and it was invaluable to us.

At the beginning of the project, we often talked about how difficult the situation is at large theatres when it comes to digital competence: One department doesn’t know what another is doing, they often work completely separately. You managed to build bridges and work with the data across departments. What are your next steps?

I actually see great value in working with digital tools: I can use the existing data sets to work in a precise manner and that gives me the possibility to approach projects differently. Or I could continue to develop the 3D model. We have created the Beethoven hall and the Werner Otto hall as 3D digital stages in Mozilla Hubs. This can be a great advantage for us as an international establishment when we communicate with our customers. Many of the requests we receive come from embassies or from overseas and this setup helps with on-site visits. Quite often, it’s not possible for all decision makers to attend the visit. A tool like ours and a list of questions can easily help to give an online impression of the space. For this purpose, we have also recreated all the equipment such as chairs, orchestra podiums, lecterns etc.

What are you hoping for in terms of digital work in your field? What is your vision? What would you need?

My dream is a virtual orchestra lineup plan! We often work with orchestra plans that have been created to scale based on the stage blueprint – but those are usually pencil scribbles and sketches. Bubbles are drawn onto these plans, but they never represent the status quo. My vision for future digital work is for visualisation tools to improve even more so they will make our planning and communication easier. Because a lot of the time, people have trouble picturing the setup – the string section over here, violas right there, and over there we have the woodwind players. That is a beautiful ellipsis that has nothing to do with reality. To make it easier for us to prepare, do our work and give a conductor an impression of the space, we can use the existing data sets to create a tool that reproduces the stage true to scale – regardless of the scaling – and also includes chairs, stands and instruments if needed. This way, someone who doesn’t know the space will have a tool that can help them develop their ideal setup, use the data sets to generate an Excel sheet and send bookings to our internal disposition software.

The interfaces are available and ready to be used. We have already taken a lot of the steps that other still need to take, so we can proceed with our projects more quickly and at a lower cost.

My goal is to continue testing methods and tools so we can stay ahead of the curve and keep making our own work easier in the long run.

orchestra setting in the „Freischütz“ production (c) Vincent Kaufmann